The latest Twitter spectacle is a water bottle. Not just any water bottle, but an insulated tumbler cup born from a 'Starbucks x Stanley collaboration.' Yes, it's still a water bottle, but one that wrought havoc on social media and at Target.

Originally targeted at dads who like to go camping, Stanley recently did a 180, shifting their focus to the millennial women demographic, successfully1. If you haven't heard of this brand before that's because for a while, it was mostly contained to this newfound demographic. But last week, Stanley released their latest: the 'Winter Pink' Stanley Quencher cup, a 40-ounce tumbler priced at $49.95. Available only at Target, the cup drew huge crowds, some lining up overnight to get their hands on it2.

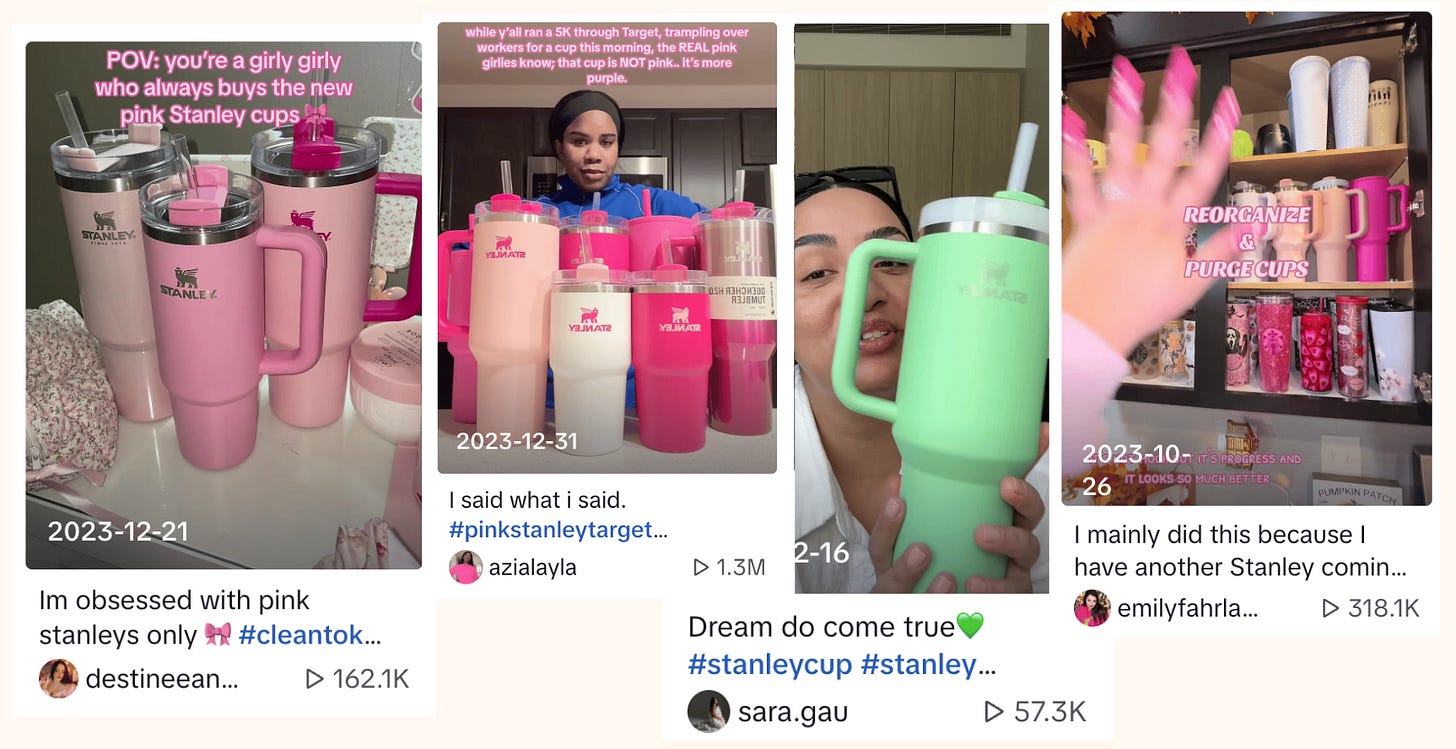

Through a mix of marketing and social media strategies - such as releasing limited editions and marketing the product as a lifestyle must-have - the cup's popularity exploded in 20233. These limited editions are now so popular that the release of the Winter Pink one led people to physically fight over it at Target. Some tried to steal it, and others to resell it for almost ten times its price - a $29k cup was even spotted on a resale website before being taken down.

Calling such a frenzy 'a trend' would be inflating the short and inflated momentum this cup is having. As youth culture Trend Analyst

told Time magazine, 'The cups are on their way out. This is peak Stanley. There’s no up from here.'4While it isn’t a trend, it is a reflection of our current girl commodification era, endless overconsumption, and virtue signalling trend patterns.

Women, as a demographic, are freakishly susceptible to marketing tactics. This was made evident by Stanley's success, which soared after Terrence Reilly, the ex-director of Crocs, rebranded the company to appeal to women. On the product level, the main changes he implemented were the addition of a range of rainbow colors to the products and releasing them in limited drops. That was sufficient to skyrocket the company’s sales within the year.

Reilly's successful tactic underscores a deeper issue: women’s identities are alarmingly entwined with consumerism. Status signalling for women goes beyond money signifiers and social class. This type of status signalling, which manifests in the determination to get the latest limited edition pink tumbler cup, reveals how vulnerable their sense of self is to the constant marketing strategies being thrown at them.

Consider the appeal of a pink water cup today and compare it to Hoover Vacuum Cleaners in the 60s. In both cases, these products offer instant validation of one’s identity. A brand new, trendy vacuum cleaner in the 60s symbolised not just belonging to the upper-middle-class white demographic, but specifically conveyed the notion of 'having it together' and being able to take care of the household.

discusses the concept of status signalling5, noting how 'elites used to distinguish themselves by what they consumed.' He points out that the high status of these products stemmed from being both expensive and useless, accessible only to the wealthy. Objects, whether gold watches, silver spoons, or insulated water bottle cups, often transcend their original utility and become vessels of meaning, belonging, and identity. In this way, capitalism and class signalling are intertwined, the first one relentlessly produces goods while the latter assigns them meaning.In our current social media era, this process is no longer confined to class, particularly for women. This is why the cup was such a hit among women. Initially, it seemed to appeal primarily to millennial middle-class white women (who are, coincidentally, Target's typical shopper6). But as the trend grew, I realized that age was no longer a factor. Women, whether millennials or Gen Z, were drawn to this cup not just for its utility but for its affiliation with trends they want to be a part of or already identify with, such as the 'WaterTok' movement - a hashtag focused on staying hydrated, with users often sharing their daily water intake, favourite hydration recipes, or showing their latest water cup.

Today, women’s identities are more plural than ever, no longer confined to the pages of a magazine. On TikTok and other social media feeds, micro ads target the multitude of identities emerging as quickly as hashtags do.

I’m not stating anything new here, but it is concerning to witness the acceleration of the commodification of womanhood. Last year's trends like 'girl math’, ‘girl dinner’, ‘girl this’, ‘girl that', though originally satirical attempts at reappropriating consumption culture, ended up being served back to us with a price tag, as seen when Popeyes introduced its own ‘girl dinner’7.

But above all else, as

concisely puts it, 'To be a modern woman is to be a PR machine.'8 All the micro trends encapsulating girlhood, be it 'that girl', 'sad girl', 'tomato girl', and others, are ways for girls to constantly rebrand themselves as if they were commodities, not human beings9, while real brands eagerly capitalize on this to offer them the latest product that will suit their newest persona. Oh, you’ve decided to be a 'water girl'? Here’s a pink insulated cup.Women are encouraged to purchase anything to reclaim a sense of personhood and individuality, for which they have been fighting for decades. We’ve failed to define girlhood beyond material consumption to the point where being a woman now means being vulnerable to the latest flash trend you’ve never even heard of before.

Being a woman in the 21st century means buying your identity online. It’s being presented with an illusion of self-determination and personal choice. It’s being granted a semblance of individualism for the sake of larger marketing schemes.

I find it hard to blame individuals for their role in corporate-funded atrocities and climate catastrophe—because it genuinely saddens me. It reminds me of my middle school days, yearning for the latest fashion to feel like I belonged with my friends. Identity and belonging are powerful forces; it's disheartening to see them being so often manipulated.

But individual choices, unfortunately, do not exist in a vacuum; they have real consequences. The bottle symbolises something larger than itself: overconsumption and its catastrophic repercussions. The irony of the Stanley cup lies in its original intent to be a reusable alternative to tackle plastic overuse, yet it ends up being another case of corporate greenwashing. When Stanley shifted its marketing focus, it became evident that the goal had shifted from saving the planet to turning the cup into a trendy, collectible item, available in a vast palette of colors, limited editions, and seasonal variants.

‘The Supreme-like craze around Stanley cups sees color releases selling out almost instantly,’ global VP of brand marketing Jenn Reeves revealed in an interview. ‘With fans eager to complete their $45 tumbler collections, one Stanley is never enough; why not ten?’ In the same interview, Reeves notes, ‘You combine [functionality] with color that matches their clothes, nails... I’ve seen them matched with kids, cars.’10

Going back to status signalling, the Stanley cup embodies a more covert agenda. ‘The Stanley Quencher has evolved beyond a water bottle into a lifestyle accessory,’ Reeves explains. This signifies how sustainability is being marketed as a lifestyle choice. The 'hydrated girlies' on #WaterTok, love showcasing a healthy image, but it's also an opportunity to virtue-signal sustainability.

#WaterTok and the display of reusable water cups fall into the trap of promoting healthy and sustainable practices, while in reality, they often hide a rainbow collection of Stanley cups in their cupboard.

Also, as a last word, let’s not forget that this collaboration item was launched during a Starbucks boycott.

Li Goldstein. 'How Stanley, the Thermos for Tough Guys, Became the TikTok Obsession of Millennial Women' Bon Appétit (2023).

Joseph Lamour. ‘Starbucks’ latest Stanley cup collaboration causes mayhem at Target’ Today (2024).

Jen Olmstead & Jeffrey Shipley. ‘5 Genius Marketing Strategies: How Stanley Mugs Took Over the Internet’ Tonic (2023).

Moises Mendez. ‘Why a New Stanley Cup Is Causing a Frenzy at Target’ Time (2024).

Erik Torenberg. ‘How Status Signaling Evolved’ Substack (2022).

Dominick Reuter. ‘Meet the typical Target shopper, a millennial suburban mom with a household income of $80,000’ Business Insider (2023).

Jordan Valinsky. ‘Popeyes is now offering ‘girl dinner.’ Here’s what’s included’ CNN (2023).

Kyle Raymond Fitzpatrick. ‘hot girl rat dinner girl lemon walk girl 💋💅👠’ Trend Report (2023).

Madisyn Brown. ‘the ‘girl-ification’ of tiktok trends: girl dinner, girl math, and more’ YouTube (2023).

Li Goldstein. 'How Stanley, the Thermos for Tough Guys, Became the TikTok Obsession of Millennial Women' Bon Appétit (2023).

"Today, women’s identities are more plural than ever, no longer confined to the pages of a magazine… All the micro trends encapsulating girlhood, be it 'that girl', 'sad girl', 'tomato girl', and others, are ways for girls to constantly rebrand themselves as if they were commodities, not human beings."

Hits the nail on the head, 100%. Especially concerning the pluralism of female identity. I wrote a little bit about this - coined it as a "Digital Diaspora" that leads to the fragmentation of the self.

Thanks, this was a great read.

absolutely obsessed you nailed this!!!!