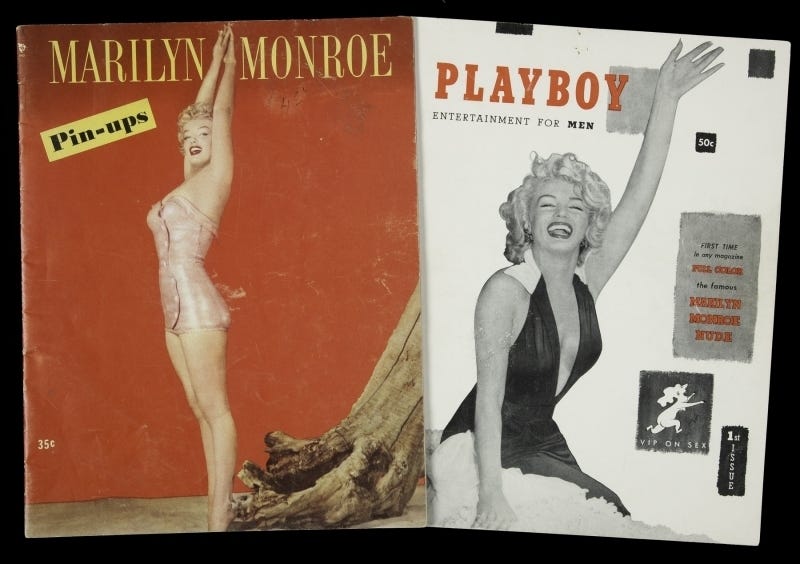

When Marilyn Monroe picked up the first issue of Playboy Magazine in 1953 and flipped through the pages, she found herself gazing at her own naked centerfold. But what should have been a moment of celebration for being the first ever Playboy Girl was one of shock; Marilyn had never posed for the magazine nor agreed to have her likeness used.1

Exploitation in Pin-Up World

To understand how Marilyn's likeness could have been so easily capitalized on without her consent, we need to take a quick look at pin-up culture.

The term "pin-up" probably evokes vivid imagery: legs at the center of the frame, bright red lips often in a surprised "o" shape, curled hair, curved body, and some revealing clothes. This is how you build a pin-up. But while the term seems to suggest anonymity, most pin-up imagery of the early 1940s came from real women. More specifically, famous actresses who men fantasized about so intensely that America's nascent mass production capabilities were harnessed to reproduce and distribute these images on a massive scale. This is how actresses like Betty Grable and Rita Hayworth found themselves "pinned" in soldiers' lockers and painted on aircrafts.2

As pin-up imagery in the 1940s was mass-produced to motivate troops, it started appearing in magazines, calendars, posters, newspapers, and postcards. So while pin-up imagery has a specific aesthetic, its massive reproducibility is what truly defines it.

Pin-Up Imagery as Simulacra

Simulacrum ( pl. : simulacra or simulacrums, from Latin simulacrum, meaning "likeness, semblance") : Originally referring to copies or representations in philosophy, were redefined by Jean Baudrillard as copies that have become so detached from their original that they "bear no relation to any reality whatsoever."3

As these images were mass-produced, the reproductions became simulacra of the original models, sometimes having their curves amplified, their clothes removed further, but especially appearing in places they hadn’t consented to pose for. The original woman's agreement to participate in one photoshoot launched a circulation of images of her likeness over which she had no control.

This is how Marilyn Monroe found herself as the face of a magazine she never agreed to appear in. Years earlier, she had done a nude photoshoot for $50 with photographer Tom Kelley, who then sold the images for $900 to a calendar production. The images were published as part of a "Golden Dreams" pin-up calendar before Hugh Hefner bought the rights from the calendar company for $500. All of this happened without Monroe's knowledge or compensation. She even had to buy her own copy of the magazine to see herself in it.

Pin-ups are based on real famous women whose identities enable both cultural and financial profit. When Marilyn posed for Kelley, she was unknown and signed with a different name to ensure anonymity. By 1953, however, Marilyn Monroe was famous, and Hefner didn't hesitate to link her identity back to the photoshoot for commercial success.

Baudrillard describes simulacra in four stages, the last being where the sign has "no relation to any reality whatsoever." During that photoshoot, Monroe was dressed differently than usual, wore her makeup differently, and signed with a different name—making the images a perfect candidate for true simulacra. But pin-up simulacra can never reach this final stage because their commercial viability depends on the original's identity. Hefner's decision to capitalize on Marilyn's fame prevented the complete divorce between the real and the hyperreal that defines Baudrillard's fourth stage.

Pin-up simulacra can never be fully achieved because the original's identity is too valuable. Sexualized images of women are infinitely more valuable when they relate to someone people fantasize about, and Hefner knew that all too well.

So, if women's identities can never be completely divorced from circulated sexualised reproductions of their likeness, the question becomes: can there be any semblance of agency over sexual simulacra?

Reclaiming Agency over Sexual Simulacra

In the midst of the Sabrina Carpenter buzz, I'd argue that she is doing just that with her album cover, whether intentionally or not.

Sabrina Carpenter clearly taps into the feminine aesthetics of pin-up culture with corset-style mini dresses and mid-century-styled hair. But in the 1940s, women had no control over becoming pin-ups—it was something that happened to them without their consent or control. So if Sabrina Carpenter were a pin-up, she'd be the final boss—one with almost total control over her likeness and its circulation.

In that sense, the very criticism people have of Sabrina Carpenter might also be her strength: she circulates sexualised imagery of herself as both model and author. While this imagery usually occurs through performance captured by her audience, she went a step further by releasing the highly controversial album cover.

The cover shows Sabrina on all fours, dolled up, looking straight at the viewer while her hair is pulled by a mysterious man who is almost entirely out of frame. The sexual nature of the image shocked many and ignited debates, but what's interesting to me is the ownership she has over the image.

It’s not Sabrina’s first rodeo with posing in suggestive poses, she hasn't shied away from posing nearly naked for various magazine covers. But unlike her usual sexual imagery, this one appears on her art—her album. This isn't an AI-generated image of Sabrina Carpenter on all fours, but an image she shot, modeled for, and used to represent her music. Sabrina is owning her simulacrum.

Additionally, the image itself is quite particular. Pin-up images usually follow one pattern: the woman is almost naked, smiling or with parted lips, and above all; she is alone. This type of imagery fits men's sexual fantasies. During the war or flipping an issue of Playboy, they could stare at Rita Hayworth or whoever they so desired and pretend she was just for them. The suggestive posture and the absence of execution (through a sexual scenario, or with the presence of another man) let their imagination fill the rest.

But Sabrina Carpenter's album cover clashes with traditional sexualized pop-culture imagery. First, she's not naked—her body is covered. But even more interestingly, she depicts a sexual fantasy that leaves little room for projection. Unlike parted-lips, nearly naked, solitary pin-up imagery, the scenario here is complete. Sabrina positions herself submissively, looking straight at the viewer, with a man's silhouette in the frame. She's already depicted submitting to a man on her own terms (dressed up and styled), removing the viewer's opportunity to let their imagination run wild. She reclaims ownership over the viewer’s sexual fantasies, imposing her own.

Subject-Object Dynamics

Sabrina Carpenter is often criticized for objectifying herself, which is considered degrading. This argument is frequently made about women who embrace feminine stereotypes and engage in sexual depictions that seem straight out of Laura Mulvey's theories.4

But something feels missing in this critique. Doesn't objectifying oneself make you, by definition, a subject? I want to make room for a Subject-Object—women who author their own objectification, who play with tropes and expectations in ways that are almost parodic. In media, I believe there is power in this approach.

There's something almost cartoonish about Sabrina Carpenter's objectification—a performance of sex and hyper-femininity so heightened that I don't think it truly appeals to men, but rather to women, queer people, and anyone who understands drag as a distorted mirror held to our expectations. As

so perfectly concludes in her essay Men don’t even like Sabrina Carpenter:“Sabrina Carpenter’s persona might have been designed to attract men, but it seems to thrive almost exclusively in female and queer cultural spaces. She doesn’t seem to resemble a blueprint of heterosexual male fantasy so much as a symbol of femininity that lives largely outside of it.”

There is agency in her process in ways that Marilyn Monroe could only have dreamed of: by owning both the origin of the sexual simulacra and an embodiment of femininity that resembles drag. A process about sexualizing herself on her album covers—on her own artistic objects that will be reproduced thousands of times but originate from her likeness and remain owned by her.

The imagery is uniquely hers, slightly off and distorted compared to traditional depictions of femininity through a male lens, ensuring that its endless circulation can never stray too far away from her authorship. It guarantees that no matter how much the images circulate in the digital universe, they remain distinctively hers.

Marie Claire UK. "How Hugh Hefner Built An Entire Empire Without Marilyn Monroe's Consent." Marie Claire, September 29, 2017. https://www.marieclaire.co.uk/news/celebrity-news/hugh-hefner-marilyn-monroe-541688

"Pin-up model." Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pin-up_model.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Referencing Laura Mulvey's male gaze theory in Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.

Further readings and acknowledgement

Thank you for reading till the end! Sabrina Carpenter is a very polarizing topic this year, and I love being able to write about and discuss her with my peers on this website and beyond. Pop culture really is fun when you get to over-analyze it for your own pleasure.

I've always loved Simulacra and Simulation as a theoretical text and lens through which to understand media. It is quite a heavy text though, so I do recommend watching this video if you are interested in understanding more:

Additionally, I recommend reading these Substack essays about Sabrina Carpenter. One is the essay I quoted earlier, which looks into how Sabrina Carpenter isn't really for men by

:The other is pretty famous on this platform, written by the incredible

. If you haven't gotten around to it, I recommend reading it—it explains how Sabrina Carpenter's aesthetics tap into cultural pedophilia, and it is, in my opinion, one of the most important essays written last year:

it’s rare to find a good analysis about sabrina carpenter’s artistry here on substack that doesn’t fall for the cliché takes, but yours is not only good, it's fantastic!

Fantastic. Loved it ☺️ xoxo